“Why not have more in X?” is an unavoidable question in a diversified portfolio. Part of the portfolio will always make you wish you owned more. And, part will always look disappointing.

In building portfolios, we review the main drivers of returns. A fundamentals-based approach, while by no means perfect, remains by far the most useful guide to understanding future return expectations.

Breaking Down Equity Returns

There are three main drivers of equity returns:

- Earnings Growth – determined by sales growth and by changes in profit margins

- Dividends – the portion of earnings distributed to stockholders as a percentage of the stock price

- Valuations – how much investors are willing to pay for each $1 of earnings, or the price-to-earnings (P/E) multiple

The chart to below shows how these components contributed to total returns over time. (Note that “Multiplicative Effects” refers to compound interest, i.e. the money you earn on the money you’ve already earned.)

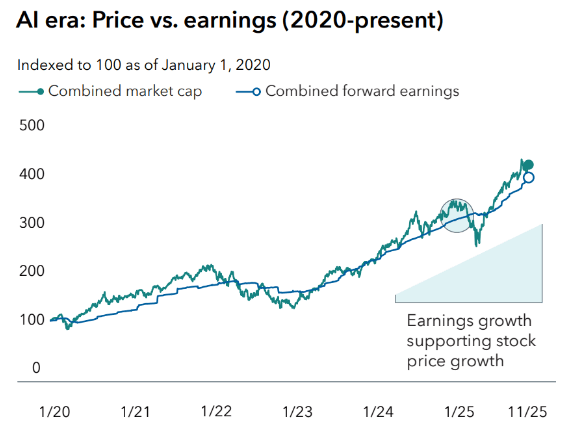

Earnings Growth

Two factors contribute to earnings: sales and profit margins. Companies can improve results for shareholders in either of two ways: increase the amount of stuff they sell or squeeze more profits out of existing sales.

Valuations

Similar to profit margins, history shows a consistent range for what investors will pay for a dollar of earnings. The price investors pay reflects how much compensation they demand for the downside risk of stocks. Today, investors demand less compensation than they historically have.

The below chart shows the S&P 500’s historical price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio. Note that the two chart peaks (2002 & 2009) happened during recessions when earnings fell off a cliff.

Since the 1920s, the average investor has paid $16 in price for every $1 of earnings. In recent decades, investors have been willing to pay more – an average of 18-19 times earnings since 1985. Today, S&P 500 investors pay 22 times earnings.

There is no formula to determine the correct price for earnings or that 22 times is misguided. Valuations reflect investor expectations, so it’s as much a behavioral question as a financial one. Valuations ebb and flow with sentiment. And as we’ve seen time and again, sentiment travels in long, unpredictable cycles from optimism to pessimism.

Our Takeaways

The best investors think in probabilities. This requires not putting full faith in any single outcome and building portfolios to survive and thrive across a range of environments.

To paraphrase Howard Marks, there is no asset so good that it can’t become a bad investment at too high a price. Our dual investment mandate is to compound clients’ wealth and remain mindful of the risks.

Get the BEW Newsletter Direct to Your Inbox

Stay informed with timely perspectives and market insights from the BEW Invest team.