What Happens if You Retire and the Market Crashes?

While it doesn’t make them easier to stomach, market downturns are normal. In fact, bear markets occur every three to four years, on average.

Long-term investors can generally take comfort in the fact that, historically, the market has always recovered from crashes with enough time. But what if time is exactly what you don’t have?

What if your portfolio plummets 20–30% within weeks of your decision to stop working and start drawing from your nest egg?

It’s an understandable and prevalent concern among recent and near-retirees.

The first few years of retirement income withdrawals involve a unique risk called sequence of returns risk: if markets fall early in retirement, you’re forced to sell assets at lower prices, locking in losses and limiting recovery potential.

It sounds alarming, but it’s entirely manageable with the right preparation.

Let’s walk through what happens if you retire during a market decline and how the right strategy can help you protect your long-term security, even in the most volatile environments.

Why Down Markets Hit Harder Right After You Retire

While still working, a market downturn is unsettling. But, in many cases, the brunt of the impact is more psychological than financial. You’re still contributing to your retirement accounts and buying shares at lower prices. There’s plenty of time for your portfolio to recover.

Retirement changes that dynamic.

Instead of buying low, you’re forced to sell low — permanently reducing the base that future growth compounds from. When you need these funds to support a 20- to 30-year retirement, that’s a problem.

Let’s look at a historical example.

Two retirees have identical portfolios: each starts with $3 million, withdraws $120,000 annually, and earns the same returns over time.

The only difference is the year they retire.

Retiree A turns in his laptop and badge in 1998, and starts drawing from their retirement account just ahead of two strong years in the market. Despite entering the decumulation phase, their account balance actually grows to $4.2 million.

Retiree B doesn’t have the same fortune. They retire in 2000, right as the dot-com bubble begins to pop. Withdrawals and losses materially drain their savings — Retiree B’s balance is almost cut in half three years into retirement.

Fast forward two decades later, Retiree A’s portfolio is six times greater than Retiree B’s.

| Retiree A Withdrawals Begin 1998 |

Retiree B Withdrawals Begin 2000 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Gain/Loss | Annual Withdrawal | Account Value | Gain/Loss | Annual Withdrawal | Account Value | |

| – | – | – | $3,000,000 | – | – | – | |

| 1998 | 26.7% | ($120,000) | $3,648,096 | – | – | – | |

| 1999 | 19.5% | ($120,000) | $4,217,133 | – | – | $3,000,000 | |

| 2000 | (10.1%) | ($120,000) | $3,681,684 | (10.1%) | ($120,000) | $2,587,868 | |

| 2001 | (13.0%) | ($120,000) | $3,097,240 | (13.0%) | ($120,000) | $2,146,145 | |

| 2002 | (23.4%) | ($120,000) | $2,261,459 | (23.4%) | ($120,000) | $1,552,533 | |

| 2003 | 26.4% | ($120,000) | $2,731,652 | 26.4% | ($120,000) | $1,810,564 | |

| 2004 | 9.0% | ($120,000) | $2,846,440 | 9.0% | ($120,000) | $1,842,546 | |

| 2005 | 3.0% | ($120,000) | $2,808,233 | 3.0% | ($120,000) | $1,774,222 | |

| 2006 | 13.6% | ($120,000) | $3,054,370 | 13.6% | ($120,000) | $1,879,527 | |

| 2007 | 3.5% | ($120,000) | $3,037,953 | 3.5% | ($120,000) | $1,821,638 | |

| 2008 | (38.5%) | ($120,000) | $1,794,833 | (38.5%) | ($120,000) | $1,046,678 | |

| 2009 | 23.5% | ($120,000) | $2,067,582 | 23.5% | ($120,000) | $1,143,984 | |

| 2010 | 12.8% | ($120,000) | $2,195,462 | 12.8% | ($120,000) | $1,154,849 | |

| 2011 | 0.0% | ($120,000) | $2,075,462 | 0.0% | ($120,000) | $1,034,849 | |

| 2012 | 13.4% | ($120,000) | $2,218,847 | 13.4% | ($120,000) | $1,037,530 | |

| 2013 | 29.6% | ($120,000) | $2,720,105 | 29.6% | ($120,000) | $1,189,119 | |

| 2014 | 11.4% | ($120,000) | $2,898,257 | 11.4% | ($120,000) | $1,190,682 | |

| 2015 | (0.7%) | ($120,000) | $2,755,991 | (0.7%) | ($120,000) | $1,063,074 | |

| 2016 | 9.5% | ($120,000) | $2,887,464 | 9.5% | ($120,000) | $1,033,043 | |

| 2017 | 19.4% | ($120,000) | $3,304,906 | 19.4% | ($120,000) | $1,090,356 | |

| 2018 | (6.2%) | ($120,000) | $2,966,166 | (6.2%) | ($120,000) | $909,606 | |

| 2019 | 28.9% | ($120,000) | $3,693,917 | 28.9% | ($120,000) | $1,017,902 | |

| 2020 | 16.3% | ($120,000) | $4,155,036 | 16.3% | ($120,000) | $1,043,801 | |

| 2021 | 26.9% | ($120,000) | $5,120,057 | 26.9% | ($120,000) | $1,172,338 | |

| 2022 | (19.4%) | ($120,000) | $4,028,046 | (19.4%) | ($120,000) | $847,764 | |

| 2023 | 24.2% | ($120,000) | $4,854,965 | 24.2% | ($120,000) | $904,101 | |

| 2024 | 23.3% | ($120,000) | $5,838,686 | 23.3% | ($120,000) | $966,878 | |

Granted, this example assumes a 100% equity allocation (not typical in retirement) and doesn’t include other income sources like Social Security benefits or pensions. But it underscores the importance of preparing for potential market declines before setting your retirement date — particularly for those relying heavily on portfolio withdrawals to cover living expenses.

That’s why retirement planning should build in safeguards against this kind of short-term shock, whether that’s through a more balanced asset allocation, a dedicated cash reserve, or a flexible withdrawal plan designed to weather market cycles.

How to Strengthen Your Portfolio Against a Bear Market

The next step is making your portfolio more resilient to sequence of returns risk. You can’t prevent a market downturn, but you can build in the flexibility to ride one out.

Revisit Your Asset Allocation

Your asset allocation (how much you hold in equities, fixed income, alternatives, and cash) plays the largest role in how your portfolio behaves during market volatility.

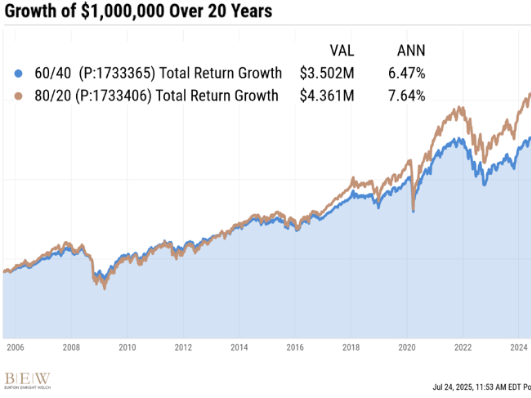

As you near or enter retirement, it’s prudent to gradually reduce exposure to riskier assets. That’s not to say you should abandon stocks entirely (they’re still your main defense against inflation and longevity risk), but aim to balance between growth and preservation.

A typical starting point for many retirees is a 60/40 portfolio: roughly 60% equities and 40% bonds. Historically, that mix has produced an average annual return of just under 7%, while its largest drawdown over the past three decades was around -30% during the 2008 financial crisis.

That kind of loss is quite uncomfortable, but not catastrophic for those who stay invested and maintain adequate short-term reserves.

Note: This isn’t a one-time decision. Revisit your allocation annually, especially after major market fluctuations or life events.

Diversify Across Accounts

A well-diversified portfolio blends exposure across asset classes as well as across industries, company sizes, and geographies. This balance ensures that when one area struggles, another can help stabilize returns.

For instance, international stocks don’t always move in lockstep with US markets, and bond funds can still serve as a stabilizing force even when short-term rates rise. Similarly, real assets like real estate or infrastructure, and select alternative investment strategies, can offer lower correlation to traditional markets, helping to cushion sharp declines.

Diversification also means avoiding overconcentration — in any single stock, sector, or idea. Many investors, notably those in the Bay Area, have large positions in company stock or tech-heavy funds without realizing how much of their future depends on one industry’s performance.

It’s important to view your total portfolio holistically, including IRAs, 401(k)s, and brokerage accounts. A financial planner can help coordinate your holdings across accounts, ensuring that each serves a purpose within your broader retirement strategy and that your combined allocation isn’t exposing you to hidden risks.

Maintain a Short-Term Reserve

Cash reserves can help absorb hits from an immediate market drop, helping you cover living expenses without selling investments at depressed prices.

A good rule of thumb is to maintain one or two years of expected withdrawals in a highly liquid, low-risk account. This could include:

- A savings account or money market fund for near-term spending.

- A short-term bond fund or laddered Treasury portfolio for slightly higher yield. Treasury interest is also exempt from state and local taxes — a material benefit for California taxpayers.

- A portion of fixed income holdings earmarked for the first few years of retirement cash flow.

If you receive Social Security benefits or pension income, these also act as additional stabilizers, effectively reducing the size of the reserve you need.

Adopt a Dynamic Withdrawal Plan

Rather than a rigid rule (e.g., “always withdraw 4%”), the guardrails approach sets boundaries on your withdrawals, adjusting them as your portfolio and market conditions change. This method allows for higher withdrawals in strong market years while still protecting against extreme downside risk.

How does it work?

- You set an initial withdrawal rate (for example, 4% of your portfolio).

- You then establish upper and lower “guardrails” at +20% and -20% of that withdrawal rate (which would be 4.8% and 3.2%) to trigger adjustments.

- If your portfolio performs well and your withdrawal rate drops below the lower guardrail, you may increase your annual withdrawal. If your portfolio declines and your withdrawal rate rises above the upper guardrail, you would reduce spending.

Let’s say you’ve recently retired with a $3 million portfolio and plan to withdraw 4% annually — about $120,000 per year, or $10,000 per month.

To maintain flexibility, you establish withdrawal guardrails: an upper limit of 4.8% and a lower limit of 3.2%.

Now, let’s see how those guardrails would respond to market swings:

If markets fall:

Suppose a market downturn reduces your retirement portfolio to $2.4 million. The same $120,000 withdrawal would be 5% of your portfolio — surpassing your upper guardrail.

To stay within range, you might temporarily reduce your withdrawal to $115,200 or less ($9,600 per month). This slight adjustment helps preserve your principal while allowing your investments time to recover.

If markets rise:

Now imagine your portfolio climbs to $4 million during a strong market year. That same $120,000 withdrawal now represents only 3% of your portfolio. In this case, you could increase your annual withdrawal and still stay within the lower guardrail.

And considering there tend to be more up years than down years, this should lead to more years of comfort than belt-tightening.

Sequence of Withdrawals: When to Draw From Each Account

Guardrails help determine how much to withdraw each year. But the sequence of withdrawals (i.e., which accounts you draw from first) can be just as influential in protecting your long-term retirement savings.

Each account type has different tax treatment, so the order matters for both portfolio longevity and annual cash flow.

Here’s a common framework to follow for most financial situations:

Start with taxable accounts

Drawing from brokerage or non-qualified investment accounts first allows your tax-advantaged accounts to keep compounding. It can also generate tax-efficient income if you sell long-term holdings or rely on dividends and capital gains.

Then move to tax-deferred accounts

Once taxable assets are depleted or rebalanced, withdrawals typically come from traditional IRAs, 401(k)s, or 403(b)s. These distributions are taxed as ordinary income, so timing matters — especially if additional income could push you into a higher bracket or trigger Medicare IRMAA surcharges.

Save Roth assets for last

Roth IRAs and Roth 401(k)s grow and distribute tax-free, making them ideal for later retirement or for legacy goals. Keeping them intact longer also provides flexibility, especially if market volatility or unexpected expenses arise.

Finding Perspective: When Is a Good Time to Retire?

Timing your retirement to avoid a downturn is borderline impossible, unless you have a working crystal ball. Fortunately, the market is positive about 7 out of every 10 years, so chances are in your favor at any given point in time.

While past performance does not guarantee future results, history is still a powerful antidote to fear. Despite recessions, wars, pandemics, and financial crises, diversified investors who stayed the course have consistently recovered and moved forward.

The difference between those who endure and those who panic isn’t luck. It’s financial planning.

If you’ve built a resilient foundation — diversified asset allocation, multiple income sources, adequate cash reserves, and flexible guardrails — you can weather stock market declines without sacrificing your goals and lifestyle.

At BEW, we believe retirement shouldn’t be defined by uncertainty. It’s your reward for years of preparation. The moment you get to choose what comes next.

We call this stage Life After Work. If you’re ready to stress-test your personal finances, refine your withdrawal strategy, or ensure your retirement savings can withstand the next downturn, download our free guide: Retirement Redefined: Your Guide to Life After Work.

Get the BEW Newsletter Direct to Your Inbox

Stay informed with timely perspectives and market insights from the BEW Invest team.