Q1 2023 Commentary

I. Bad News Beats Expectations

Investors’ concerns entering 2023 included inflation, whether the Fed will trigger a recession, and war in Ukraine. All remain worries.

Then, suddenly, mid-March brought the second and third largest bank failures in U.S. history. As if investors weren’t already uneasy, discussion turned to “financial system contagion”, a term reminiscent of the Great Financial Crisis.

And yet, through March 31, U.S. and international stocks are both up 7% year-to-date. This is on the heels of a strong end of 2022.

Why aren’t stocks going down? The near-term landscape is full of obvious risks and precarity. Shouldn’t the market reflect the dark horizons?

In a few senses, it already does.

The S&P 500 is still 14% below its January 2022 high.

The yields for 1 and 10-year Treasuries are 4.6% and 3.4%, respectively. This inversion (shorter-term bonds usually yield less than longer-dated ones) reflects belief that the economy will sour, causing the Fed to lower rates.

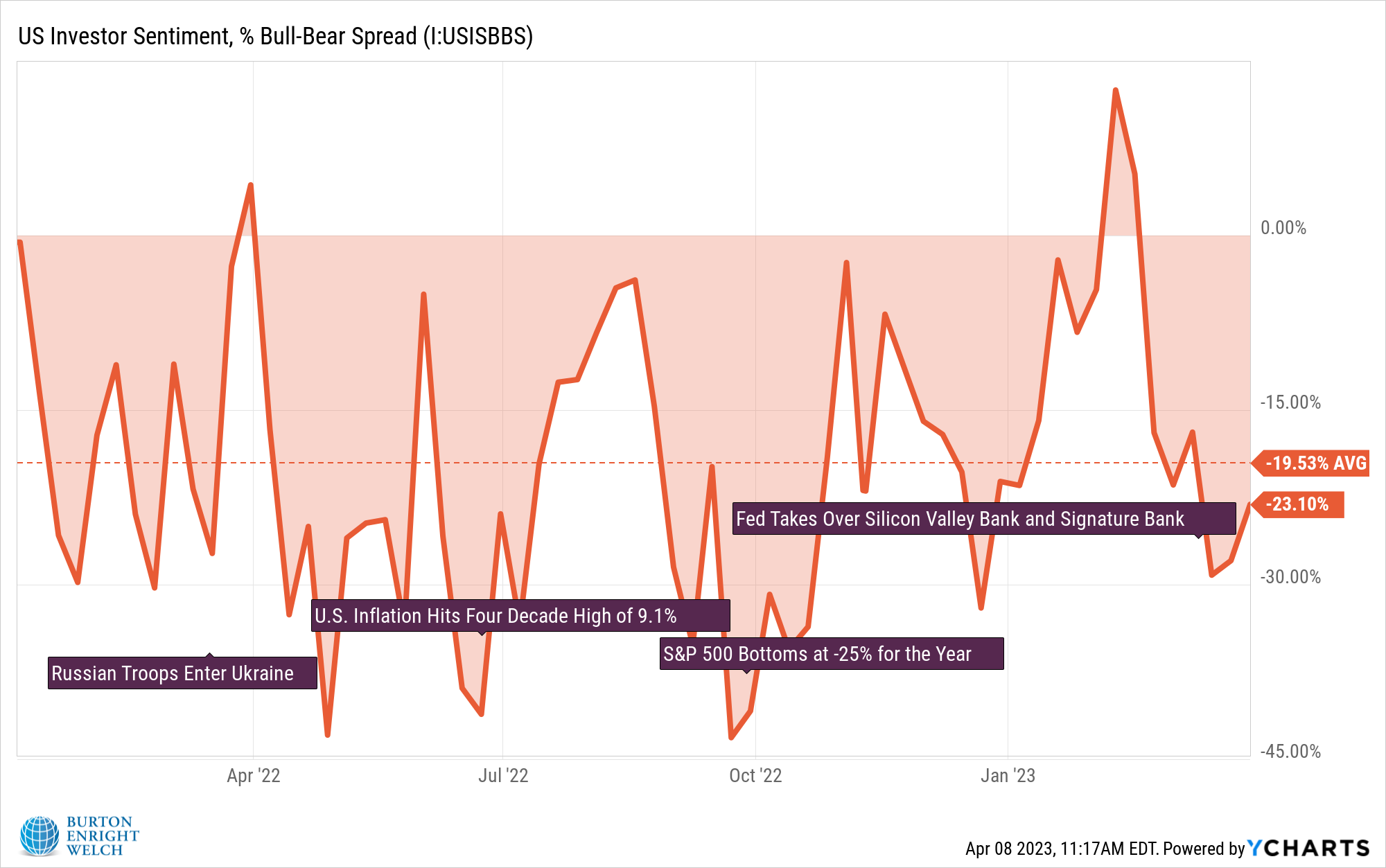

Investor sentiment remains gloomy. The following chart shows a weekly investor survey, asking whether investors are “bullish,” “neutral”, or “bearish”. Since January 2022, there have been only three weeks with more bulls than bears, and the average result has been 20% more bears than bulls.

Perhaps, widespread negativity is helping hold up the market. With pessimism as a starting point, there’s less potential for bad news to drive sentiment and prices even lower.

The last six months defy those who wait until circumstances improve before investing. Sometimes, the market goes up because of good news. Sometimes, it goes up because the bad news is no worse than what investors already expected.

II. More Lessons in Diversification

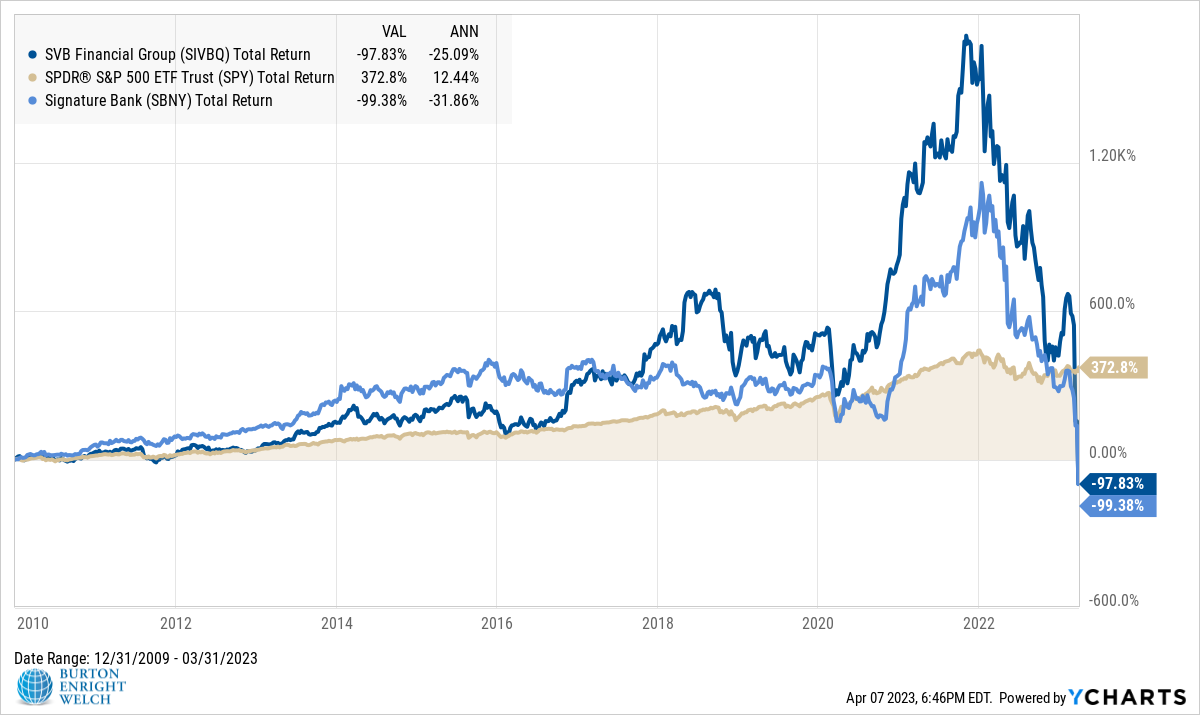

The collapses of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), Signature Bank, and Credit Suisse did not imperil their depositors, but they devastated their shareholders. Stock worth a combined $85 billion in January 2022 will end up nearly worthless.

The banks present yet more lessons on the dangers of single stock concentration.

Credit Suisse was founded in 1856, meaning it survived the Great Depression, dozens of European wars including two World Wars, and countless other crises.

In May 2007, a month before the first iPhone release, Credit Suisse had a $90 billion market capitalization (the total value of all stock) versus a $86 billion market cap for Apple. With a global brand, storied legacy, and a soaring financial sector, many would have guessed Credit Suisse would be the $2.6 trillion company that Apple is today.

Unlike SVB and Signature Bank, Credit Suisse did not implode overnight. A series of scandals and bad decisions brought the stock lower and lower. Many tried to buy the dip, and there were A LOT of dips.

From 2010 through 2021, $100,000 investments in SVB, Signature Bank, and the S&P 500 would have turned into $1.4 million, $753,000, and $481,000 respectively. Then, meteors struck.

These are extreme examples of single stock risk. Nonetheless, they represent part of the spectrum of possible outcomes for any stock.

Diversification does not provide the potential highs of single stocks. But that is more than made up for by avoiding the potential lows.