People like stories. Stories need drama.

Some quarters deliver it in spades. This spring, we had Liberation Day and the Tariff Tantrum.

Last quarter was different. Markets climbed from start to finish. Stocks and bonds. U.S. and international. Large cap and small cap. All higher.

But there was not much drama. And when markets don’t provide tension, commentators create it.

Reenter bubble chatter.

“U.S. Stocks Are Now Pricier Than They Were in the Dot-Com Era”

-Wall Street Journal

“This Warren Buffett indicator is bright red. Why it could be worse than the 1999 bubble – and how to prepare.”

-Yahoo! Finance

“AI Bubble Today Is Bigger Than the IT Bubble in the 1990s”

-Apollo Global Management

Granted, there are no shortage of scary charts to support these headlines.

The Shiller CAPE ratio, which compares stock prices to the last decade of inflation-adjusted earnings, has been a strong guide to long-term returns. Today, it’s at the highest level since the Dot-Com peak.

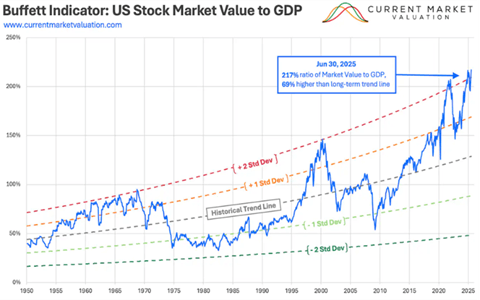

The Buffett indicator, which compares the stock market to the size of the economy, tells a similar story. Warren Buffett’s logic was simple: over time, corporate profits can’t outgrow the economy that supports them. Today, the indicator is far above its historical trend.

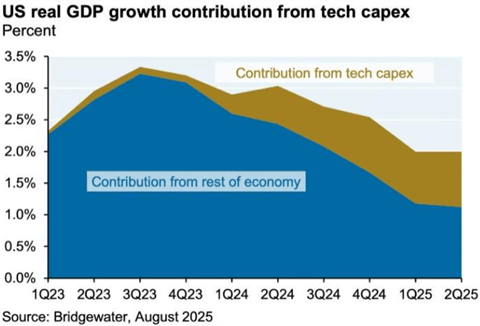

The data on the Artificial Intelligence (A.I.) infrastructure boom is even more striking. About half of the U.S.’s economic growth comes from building data centers for Artificial Intelligence.

For perspective: from 1960 to 1973, the Apollo program spent about $300 billion in today’s dollars to go to the moon. Tech companies will spend about $400 billion on AI infrastructure this year.

We could keep going. But we may be stoking nerves, which is the opposite of what we’re here to do.

Our real point is that the story is less certain than the scary charts suggest.

Bubble talk often assumes unsustainability and inevitable reversion to past trends.

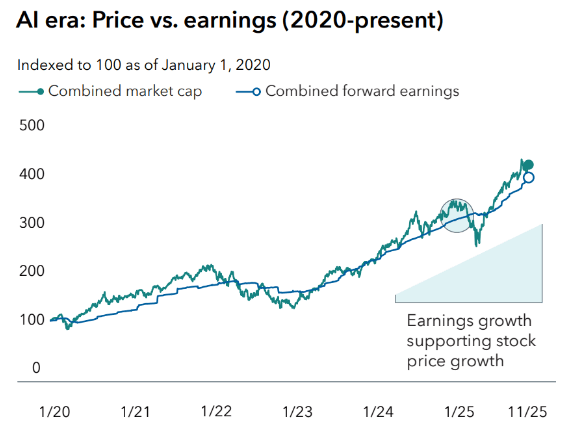

Valuations matter. They remain one of the best guides to expected returns. Yet, they do not foresee a crucial variable – future profits.

Today’s prices, elevated as they are, can prove to be reasonable if corporate profits grow substantially.

A decade ago, the rise of FANG stocks (Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, Google) and splashy IPOs from unprofitable unicorns (>$1B startups, e.g. Uber and AirBnB) fueled warnings of another bout of tech overexuberance. The CAPE ratio reached 26, second only to the Dot-Com bubble.

Yet, the ensuing ten years showed that the 2015 market was not expensive. Extraordinary earnings growth ended up justifying the 2015 prices, a reminder that high prices don’t always mean unsustainable ones.

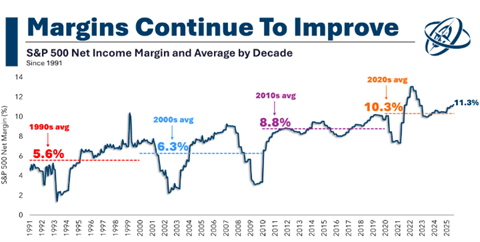

Some who believed the mid-2010s market was elevated cited eventual lower profit margins. Textbook economics says that profit margins should fall back to long-term averages as competition, costs, regulation, and business cycles erode high margins. Instead, they’ve kept climbing, decade after decade.

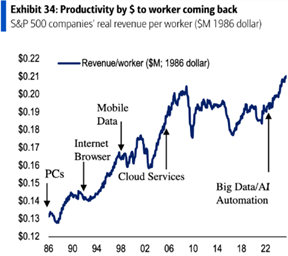

One reason: technology keeps driving productivity. The A.I. thesis is that this force will only accelerate.

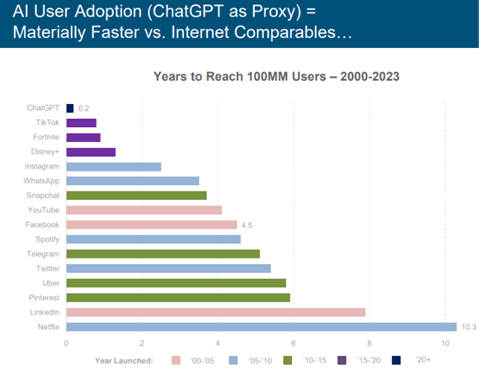

And unlike the internet, which took many years to fulfill its early promise, A.I. optimists believe the payoff will arrive quickly.

Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg captured the A.I. optimist sentiment a few weeks ago:

“If we end up misspending a couple of hundred billion dollars, I think that that is going to be very unfortunate obviously. But I actually think the risk is higher on the other side. If you build too slowly and then super intelligence is possible in three years, but you built it out assuming it would be there in five years, then you’re just out of position on what I think is going to be the most important technology that enables the most new products and innovation and value creation in history.”

This quote could one day be paraded as proof of mid-2020s A.I. delusion. Or it could mark the early recognition of an imminent wave that transforms profits and value creation.

What to do?

We are not going to chase either narrative. We won’t go all-in on the A.I. wave. And we’re also not going to swing the other way and bet on a bubble bursting.

Instead, we’ll stay diversified. Our portfolios include a meaningful allocation to the A.I. behemoths. It’s likely that the massive A.I. buildout will create winners. No one knows exactly who those winners will be, so owning the broad basket ensure we benefit from whoever emerges.

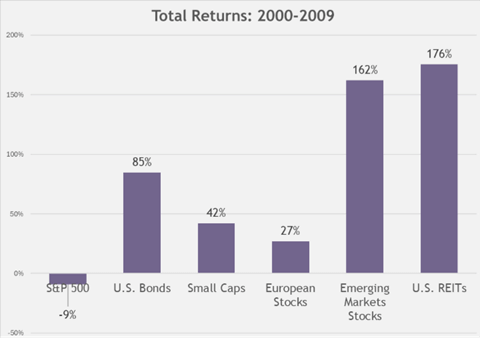

Still, it’s an open question how much and how quickly A.I. will change the economy. That’s why diversification remains essential. If the next decade rhymes with the 2000s, then diversification will shine.

Every era invents narratives to rationalize market strength. In the 2010s, it was low interest rates and quantitative easing. This decade, it’s government spending and the AI build-out.

Markets are pricing in a surge of profits from A.I. That outlook may prove accurate. Or, it may turn out to be early and overblown.

Either way, our role is not to guess, but to build portfolios resilient enough for both outcomes.

Headlines will always chase drama. Portfolios should not. We keep our clients invested in the story that matters – steady, long-term progress.

Get the BEW Newsletter Direct to Your Inbox

Stay informed with timely perspectives and market insights from the BEW Invest team.